Welcome to the Topaz WWII Relocation Center, a site steeped in history and an enduring symbol of resilience and reflection. Located in the stark landscape of central Utah, this former internment camp tells a powerful story about a challenging chapter in American history.

Our journey begins in the early 1940s against the backdrop of World War II. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States entered the war, and fear spread across the nation. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, setting in motion the forced relocation and internment of Japanese Americans and those of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. This decision led to the establishment of ten relocation centers, with Topaz being one of them.

Construction of the Topaz Relocation Center, originally named the Central Utah Relocation Center, began in July 1942. By September of the same year, the camp officially opened its gates, eventually becoming home to over 8,000 internees. These individuals, primarily from the San Francisco area, were thrust into a harsh desert environment, facing extreme weather conditions that were a far cry from their coastal homes.

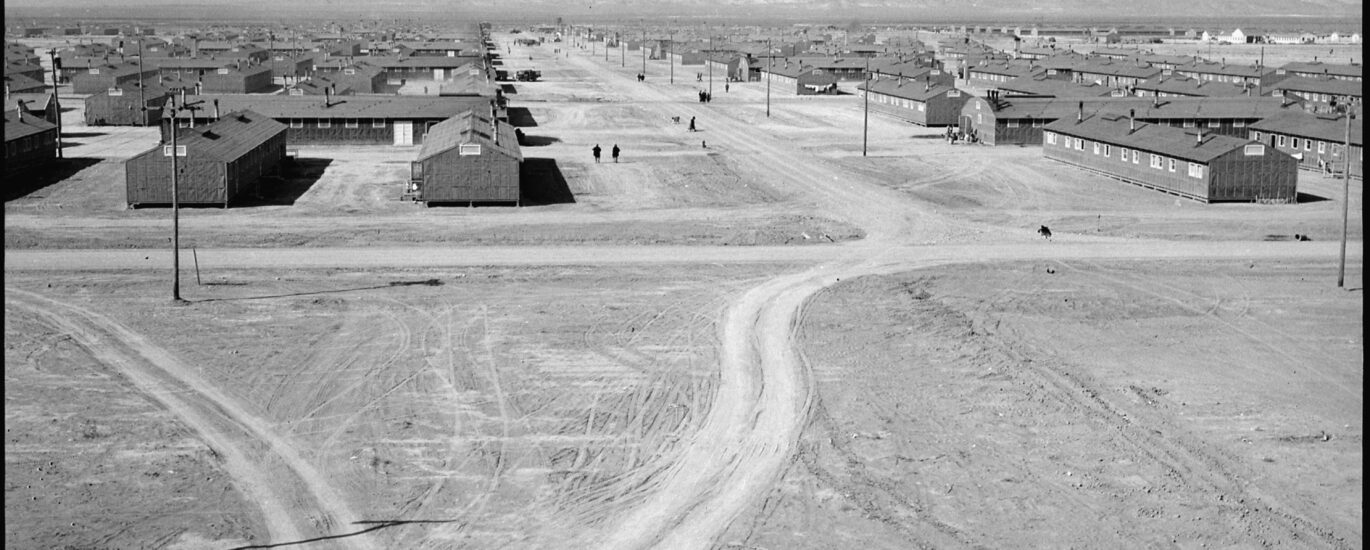

The camp spanned over 19,800 acres, with a central area covering one square mile. It included 42 blocks, each with 12 barracks, housing between 250 to 300 people. Life at Topaz was challenging, with the internees living in bare-bones accommodations made from pine planks and tarpaper. Despite these conditions, the community within the camp thrived in its own way. They built furniture, planted trees, and engaged in extensive landscaping to make the harsh environment more bearable.

Education and culture found their place within the confines of Topaz. The camp boasted two elementary schools, a junior/senior high school, and hosted various cultural activities. Among the notable figures interned here was Chiura Obata, a renowned artist and art professor at the University of California, Berkeley. His work during his internment captured the beauty and desolation of the landscape and offered a poignant reflection of life in the camp.

As we stroll through the site today, remnants of the camp’s infrastructure, such as building foundations and portions of the perimeter fence, serve as silent witnesses to the past. The Topaz Museum, established years later, plays a crucial role in preserving this history. Born out of a high school project led by teacher Jane Beckwith in 1982, the museum emerged from the community’s desire to remember and learn from this period. It houses hundreds of artifacts, photographs, and oral histories, providing a vivid account of the lives and stories of those who were confined here.

Through the museum’s exhibits, visitors gain an understanding of the systemic racism and constitutional violations that led to the internment and the resilience of those who endured it. The artwork, personal stories, and photographs on display connect us to this shared history, urging us to reflect on civil liberties and justice.

Today, the Topaz site and museum stand as reminders of the past’s injustices and the enduring spirit of those who lived through them. As we explore these grounds, we honor their stories and commit to a future that upholds the values of freedom and equality for all.